***** (5 Stars) – click here to read on The Guardian.

Group fires up chilly night before 10,000-strong crowd with blistering 24-song set that belies their decades as a fixture on Australia’s rock’n’roll landscape

Petersons Winery, Armidale

Sun 6 Oct 2024 13.32 AEDT

On the screens flanking the stage at Petersons Winery in Armidale, you can clearly see the scar at the top of Jimmy Barnes’ big barrel chest. It’s a visible legacy of the singer’s second round of open-heart surgery in December last year, after a serious bout of bacterial pneumonia nearly killed him.

Two months ago, he had a hip replacement that also left him fighting off an infection, which kept him tethered to a drip for weeks. You wouldn’t know it. Watching him tear through Cold Chisel’s 24-song set on the first official stop of their Big Five-0 tour, Barnes looks indestructible. At this rate, he’ll outlive all of us and Keith Richards combined.

They share some history, this town and Chisel, having solidified here in 1974 while primary songwriter Don Walker was completing a degree at the University of New England. Nearly 1,000 metres above sea level, a crowd of well over 10,000 (many of them grey nomads who have travelled from far and wide) huddles in the chilly night air.

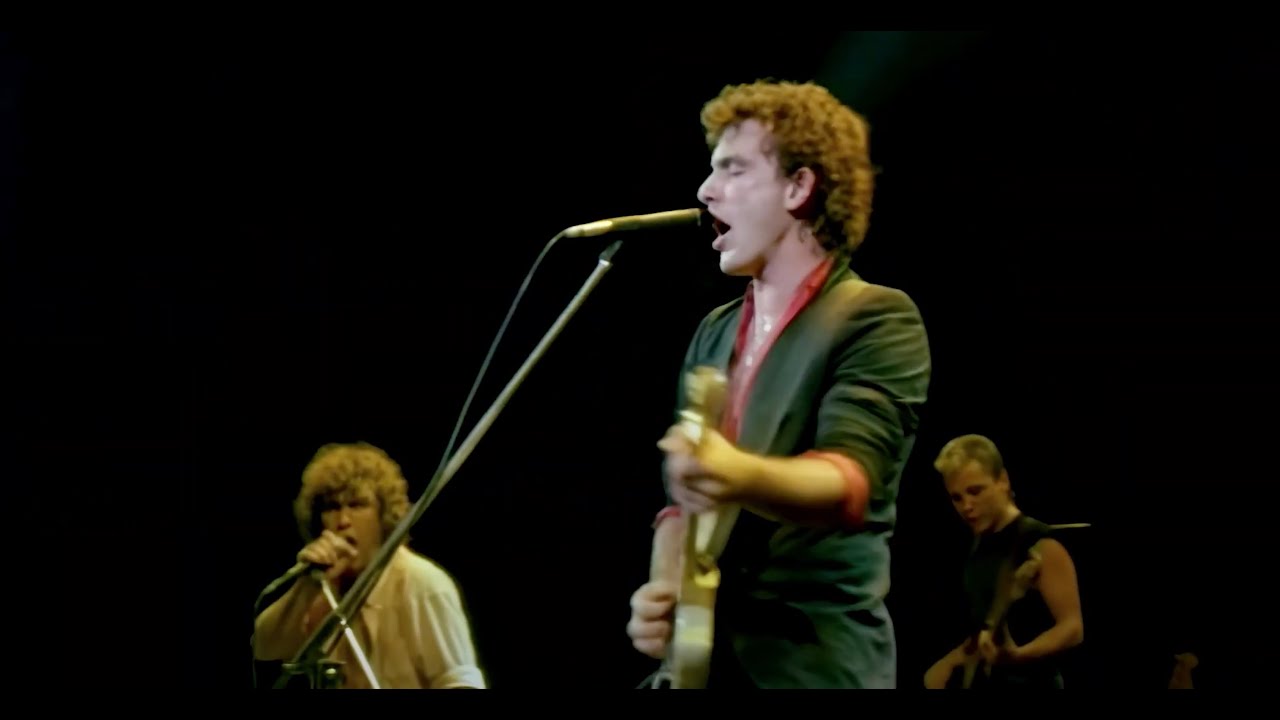

Photograph: Robert Hambling

As usual, they open with Standing on the Outside. It’s a song about the impossibility of trying to get ahead when everything is stacked against you: “No amount of work’s gonna get me through the door.” It shakes and rattles like one of the great old 50s rockers, but its hard-bitten sentiment is unlikely to have ever been more relevant. The audience erupts.

Barnes – dressed, like most of his bandmates, in basic black – is in his element. Born a street fighter, he has five decades of ring generalship to draw on. He doesn’t waste an inch of the stage. And his voice is superhuman, pitch-perfect, drawing from deep within himself and the bottomless well of the songs.

When guitarist Ian Moss steps up to sing Choir Girl, followed by the lengthy One Long Day from Chisel’s 1978 debut, it’s a reminder of this band’s exceptional vocal firepower. Moss, a magnificent singer in his own right, could have fronted any band in the world, and like Barnes he sounds in better voice than ever.

Photograph: Robert Hambling

But this band is a premiership-quality team. When The War Is Over and Forever Now follow each other in the set. Both of them were written by Steve Prestwich, the band’s drummer who died in 2011. These are two of Cold Chisel’s most poignant songs. Bassist Phil Small can lay claim to My Baby, their most straightforward and sincere detour into pop.

Barnes rips through Rising Sun, his celebratory paean to his wife Jane. A few songs later comes You Got Nothing I Want, his equally celebratory fuck-you to the American record company executive who sacked the band after hearing it. The song finished them in the US, but has become part of their legend in Australia, and it’s a story Barnes still tells with relish.

It’s Walker, though, who is Chisel’s gravitational force. Behind his keyboards, he keeps his head down, with a quiff of white hair you could see for miles. “Play that fuckin’ piano!” Barnes tells him, and he pounds it like Little Richard for the closing Goodbye (Astrid, Goodbye).

But before that comes the reggae shuffle of Breakfast at Sweethearts, a song so vividly drawn that you can smell the coffee. There’s the grimy blues of You Got to Move, which originally appeared on Walker’s solo album Lightning in a Clear Blue Sky. And, of course, there’s Khe Sanh, an Australian answer to John Prine’s strung-out Vietnam veteran Sam Stone.

Photograph: Robert Hambling

As the years have gone by, Flame Trees has become a song even more tightly held by its audience. The lift in the bridge still makes my hair stand on end: “Do you remember, nothing stopped us on the field in our day?” It’s a lyric that implies so much, because all its boozy reverie determinedly averts its gaze from the elephant in the room.

Although it’s not acknowledged by the band, there’s a collective understanding that this could be the last time. Many years separate Cold Chisel tours now; Walker, the oldest member of the group, is 73. The audience spans generations, but it’s fair to say the majority have grown up, and grown old with them. If there’s a next time, we won’t all be here to see it.

But as Jimmy appears immortal, so too these songs – long since embedded in the national consciousness – will endure. Bow River ends the main set, Moss taking the first half of the song before Barnes swoops in behind him and tears it to shreds. The pair of them are grinning like loons, ecstatic, and they leave the audience emotionally spent.

![[link href = https://coldchisel.lnk.to/TheBestOf]Latest Release[/link]](https://www.coldchisel.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Cold-Chisel-50-Years-The-Best-Of-610x610.jpg)