Dead-end jobs in the bank and the public service; countless drunken nights at the Stardust Hotel, Cabramatta; clumsy experiments with drugs and girls; north coast summer holidays; terrible early morning pizzas at Fairfield station; not caring too much about anything but the nights and the weekends: The suburban blues and a thousand Cold Chisel shows.

“Here lies a local culture/Most nights were good, some were bad/Between school and a shifting future/It was the most of all we had,” wrote Don Walker in “Star Hotel.” It was the summer of 1980, I was leaving school and learning fast. If “Star Hotel” was written about Newcastle, it was just as relevant to the western suburbs of Sydney, and like so many others I could have been his “uncontrolled youth in Asia.” All aimless naivete and enthusiasm, the only thing I knew was that down the road somewhere there’d be “girls, visions, everything” and Cold Chisel was the only authentic soundtrack.

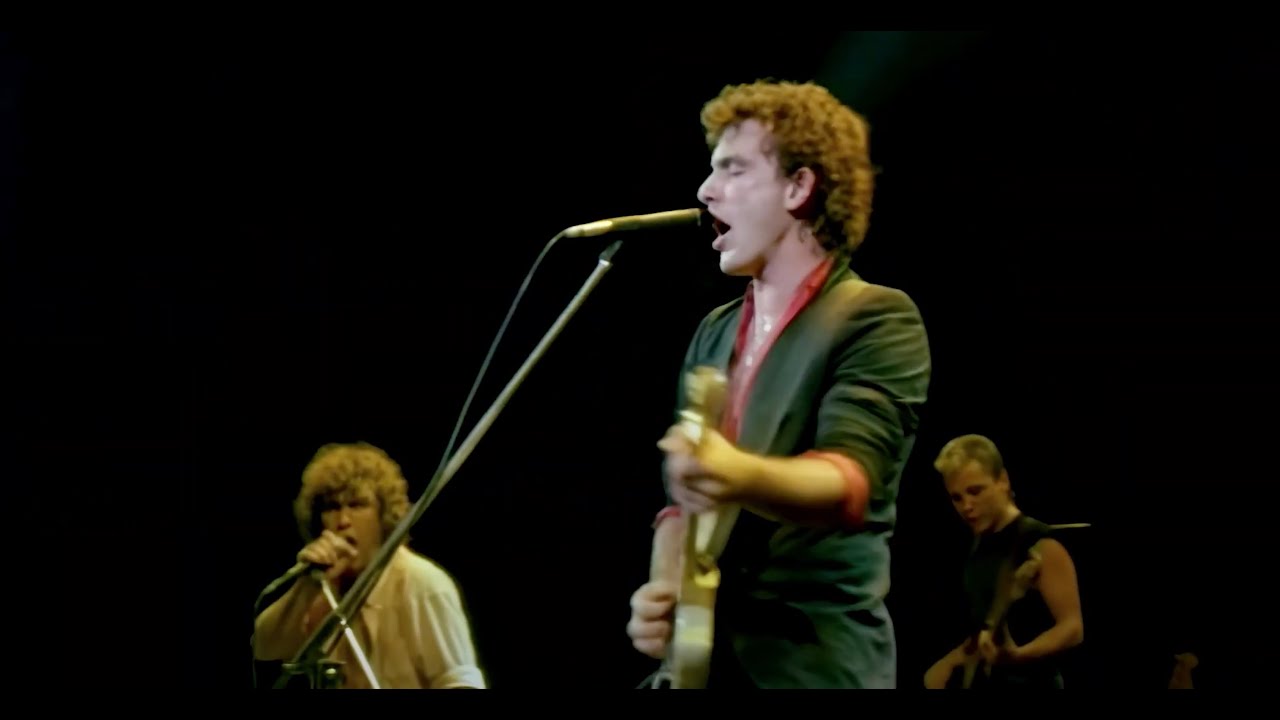

Memories, still incredibly vivid … Barnes, all vodka, limbs and spastic abandon being dragged out of the crowd at the Playroom on the Gold Coast during “Wild Thing.” Martin got his car kicked in that night, probably ’cause it had N.S.W. number plates but after that performance no-one seemed to care … Having a stand-up fight with some bloke from the office, me swearing that Don Walker was the best songwriter this country ever produced, him mouthing off about this old fart, Brian Cadd; Walker playing great rockabilly piano on “Don’t Let Go,” on the Youth in Asia tour, stealing the song from Isaac Hayes, returning it to Jerry Lee….lan Moss, Chisel’s only real virtuoso, doing the most soulful version of “Georgia” during The Last Stand run, and always “One Long Day”…Buying East on the first day of release to make sure I got the bonus single, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”/”The Party’s Over”; playing Swingshift three times in a row the day it hit the stands, getting stoned for the first time ever that night and playing it some more….Calling in favours from Mark Pope, an old family friend, when he became Chisel’s tour manager, getting my name on the guest list four nights in a row around the time of Circus Animals….Chisel under the bigtop on the Circus Animals tour, mixing lions and tigers with the powerful, primal rhythms of Phil Small’s bass and Steve Prestwich’s drums on “Taipan” and ‘Wild Colonial Boy,” and Barnes screaming “Goodbye (Astrid Goodbye),” riding pillion with a daredevil motorcyclist on a tightrope.

Cold Chisel figured in the lives of so many because Don Walker articulated and Jim Barnes embodied the blurred mess of the Australian urban/suburban experience, and simply because they were the most feral and beautiful pub rock & roll band in the world.

If, in the Sixties, Australians had generally mimicked the Merseybeat sound and during the Seventies, U.S. heavy metal and west coast soft pop, Cold Chisel broke with the tradition, defining a peculiarly Australian fusion of pub rockabilly, metal and rough-house soul and blues with Walker’s tales of loners, losers and lovers moving across the country. “Khe Sanh,” their first single, set the tone. A wordy ode to the disillusionment of an Australian Vietnam vet, it embodied the contradictions of Cold Chisel: if they were regarded by many as meat and potatoes hard rock, this was a subtle arrangement, all the more emotive for Dave Blight’s fantastic harp, and it pulled no punches lyrically, illuminating the hardened detachment of the character, who just couldn’t look at life the old way anymore. It was banned on radio for its depiction of girls whose, “…legs were often open/But their minds were always closed,” and probably for its reference to ‘hitting some Hong Kong mattress all night long’. I don’t know whether Chisel were ever advised to edit it, but doubtless they would have refused, and rightly too. The song still managed to climb to something like 24 on the charts, and remains one of the most requested Australian songs on the airwaves. Chisel were the first Australian band whose lyrics I pored over, and they were invariably worth it. Intense treatises like “Star Hotel” and “Letter To Alan” were balanced by the light cynicism of “Ita”, great throwaway lines like “If your head needs a bandage/ Try a roadhouse open sandwich,” and “She played Mozart with my feelings/And havoc with my face,” and always a wicked sense of the carnal. Walker obviously had a healthy respect for Chuck Berry, with his songs rooted in times and places it made them believable, relatable. “Home and Broken Hearted” is all the more meaningful because it travelled through Adelaide, Sydney, Euston; anyone could have breakfast at Sweethearts; I hitch-hiked “through Nambucca, up the coast”; these aren’t songs about the rock star life.

And Chisel, of course, could play it better than anyone, and always did. They always went for the throat, living totally in the moment, Moss’s guitar leading the way, Walker’s piano and the rhythm section powering forward relentlessly, Barnes bringing them down, “shhh, shhh,” on “Merry-Go Round,” and then “1,2,3,4,” exploding back again. And if they are primarily remembered for the ragged glory of their pub shows, they were equally capable of turning hard rock or rockabilly around on a dime, to then play one of Steve Prestwich’s great pop tunes, “When the War is Over” or “Forever Now.”

Cold Chisel refused to play the industry games or bow to foreign gods. The days of persisting and believing, in Adelaide, Armidale and Sydney, and the relentless touring toughened them and while “no compromise” is a tired worn rock & roll cliche, I can’t think of any concessions they made, and ultimately, with the mega-success of East and continual house-full gigs they turned an initially unwelcoming industry into their lap dogs. I remember their appearance at the 1980 Countdown/TV Week rock awards, April 1981. The band had scooped the awards on the back of the runaway success of East, but they weren’t comfortable as the ‘Kings of Pop,’ venting their frustrations by refusing to personally pick-up any of the awards and closing the evening with a brawling re-working of Barnes’ rockabilly gem “My Turn To Cry,” which, in its re-written verses, damned the awards and savaged TV Week for its superficial support of the music industry and its sudden embracing of the band. As Barnes screamed something like “You won’t find me on the cover of your TV Week” and repeated “Where were you (when we needed you)?” the band demolished their instruments and the set, a la the Who. It was probably Cold Chisel’s most confrontational and controversial public moment and it drew the line. If you didn’t get it, you didn’t get Cold Chisel.

Quality and integrity will always win out, Don Walker recently told me, and he’s right. Cold Chisel didn’t dress up for anybody. In the early 80s, amongst a sea of haircuts, they were just blokes. Barnes in a football jersey in the video for “You Got Nothing I Want,” Phil Small always in straight street clobber, Moss dripping sweat like a tap from the first song on, at every show. Their records were/are the same. They eschewed gimmicky production, relying just on songs and performance. And it’s why they’ve last – there’s a certain truth in the grooves that’s real and timeless. It’s why radio continues to flog “Choirgirl”, “Flame Trees,” “Khe Sanh,” “Forever Now,” “Saturday Night”…and it’s why the live tracks here still cut through.

Anyway, I guess they put it better than I ever could: “And if I don’t hang around/Our old gambling grounds/It does not mean that I’ve forgotten/We believed… And I still do.”

John O’Donnell, 1991

![[link href = https://coldchisel.lnk.to/TheBestOf]Latest Release[/link]](https://www.coldchisel.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Cold-Chisel-50-Years-The-Best-Of-610x610.jpg)